|

|

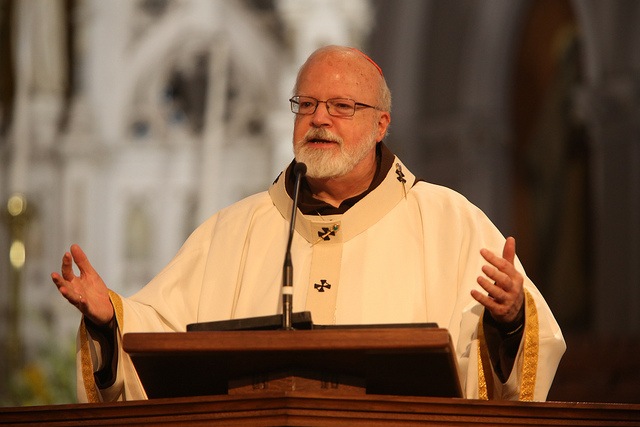

Photo credit: George Martell/Archdiocese of Boston |

|

The basis for our ministry in life has to be our friendship with Christ. Kissing the altar cannot be a formalistic or empty gesture. It must betoken our attachment to Christ, our loyalty to him, our friendship. In the liturgy of St. John Chrysostom before receiving Communion, the priest prays: “Of thy mystic supper receive me today, O Son of God, as a partaker; for I will not speak of the mystery to thine enemies; I will not kiss Thee as did Judas; but as the thief, I will confess Thee: “Lord, remember me in thy kingdom.” Judas’s kiss was a lie. It did not betoken friendship and love for Christ, but rather love of power and money. The authentic priestly kiss is one that betokens self-emptying and renunciation for the sake of the Beloved. I always like to say that poverty does not always lead to love. But love always leads to poverty. Our love of Christ must lead us to embrace his kenosis. As we renew our priestly vows today, let us be mindful of how these promises can deepen our friendship with Jesus. Our fidelity to prayer and to our commitment to celibacy can draw us closer to Christ, the High Priest and Bridegroom. Ironically enough, in today’s world where fewer people are getting married, more people attack the Church’s practice of celibacy. Often times in our culture the avoidance of marriage is based on a will to live for oneself and therefore is a no to the bond of marriage. Celibacy is meant to be the opposite: it is a definitive yes. It is to give oneself into the hands of the Lord. And therefore, it is an act of loyalty and trust, and that also implies the fidelity of marriage. Celibacy is a sign of the presence of God in the world, a reminder that God is to be loved above all else. The pastoral life of the Church has benefited greatly from the generous availability of men and women who have embraced a vocation of celibacy. I know of a wonderful, faith-filled, young couple who are both doctors and want to be missionaries. They asked me to suggest different missions where they might go to offer their gifts and serve the poor. I put them in touch with bishops in Papua New Guinea and in Paraguay. In the end they came to me and said it would be impossible for them to go to those countries because they want to have children and they worried about zika. I certainly understand the logic. When I was in seminary and three of my classmates left for Papua New Guinea, they were told: “you are going to get malaria, dengue, leeches, and fleas. Not necessarily in that order, but you will get them all.” I daresay if my classmates had wives and children, they would have had to think long and hard before answering the call to go to Papua New Guinea. Our celibacy is to make us even more available to love Christ and service people. Theologically it is meant to be the sign of Jonah, the sign of the Resurrection. That we are all called to live forever and therefore it is not necessary for everyone to have children in order to live on in their posterity. A priest is above all, a friend of Christ. Our love for Him is what draws us to our vocation and allows us to find meaning and purpose in our ministry. We kiss the altar as we approach and we kiss it as we leave, just as a husband kisses his wife when he comes home and kisses her when he leaves. In the Maronite liturgy there is a beautiful apostrophe the priest addresses to the altar before leaving at the end of Mass. The priest says: “Remain in peace, O holy altar of God. I hope to return to you in peace. May the offering I have received from you forgive me my sins and prepare me to stand blameless before the throne of Christ. I know not whether I shall be able to return to you again to offer sacrifice. Guard me, O Lord, and protect your Holy Church, that she may be the way to salvation and the light of the world. Amen.” And when a Maronite priest dies, his brother priests carry the coffin, walking around the altar praying this prayer of farewell to the altar. Gospel Book The next kiss a priest bestows is after the proclamation of the Gospel. He kisses the Word of God as he prays: “Per evangelica dicta deleantur nostra delicta.” “May the reading of the Gospel cleanse me of my sins.” The priest is a man of the Gospel. Jesus’ words and actions are what must mold the priest’s heart so that he may become an icon of the Good Shepherd. In today’s Gospel Jesus tells us that He has been anointed to announce the Gospel to the poor and the downtrodden. We priests are also anointed to be heralds of the same Gospel. We are ordained to be missionaries on fire with the desire to share the good news with everyone. Christ has called us to be fishers of men and too often we are keepers of the aquarium. We must meditate on the Gospels frequently so that the words and the inflections of the voice of the Good Shepherd become our own. Our role as preacher and teacher is crucial. We must be constantly preparing for this responsibility by our life of prayer, study, and reflection. Everything a priest does should teach the Gospel. Our words, our actions, our attitudes. Being a missionary is born of a constant struggle to deepen our own conversion; so that like the Baptist we can say, I must decrease, He must increase. Kiss of Peace Having kissed the Altar, and the Gospels, the next kiss is bestowed on the Bride of Christ, the People of God, our brothers and sisters whom we are called to serve. We must love our people and share their life. It is not a matter of being popular, but of being a spiritual father. In the film Ryan’s Daughter, there is a touching portrayal of a parish Priest, Father Hugh Collins, who demonstrates such concern for his people in an Irish village during the uprising. His constant companion is a man who is developmentally challenged, Michael. When the village rises up against Rosy Ryan, accusing her of being a collaborator with the British, they beat her and cut off her hair. It is her pastor who protects and consoles her. As priests we need to have a special love for those on the margins, on the periphery as Pope Francis is wont to say. We need to love our people and help them find meaning in life, to discover their purpose and embrace their mission. We must emulate the Curé of Ars who used to pray to the Lord: “Grant me the conversion of my parish, and I accept to suffer all you wish for the rest of my life.” St. John Vianney did everything he could to pull people away from their own lukewarm attitude in order to lead them back to love. The Kiss of Peace is part of the liturgy from the earliest centuries and is a stark reminder that we are priests not for ourselves, but for our people. We must love them as the Good Shepherd who lays down His life. It is only when they know that we love them that they be willing to listen to us and accept our message. Yes, even the message of the Gospel can be rejected because of the messenger who does not know how to communicate the Gospel with love, with a kiss. The Cross The last kiss is at the veneration of the Cross which is part of the Good Friday service. We live in a culture that sees pain and suffering as the greatest evil. This attitude has helped spur the opiate crisis. We are often like Peter who tries to keep Jesus from even talking about the Cross. Jesus rebukes St. Peter: “Get behind me Satan. Thou savorest of the things of men and not of God.” And like Peter we often flee from Gethsemane and Calvary. To savor the Cross is to savor the things of God. At our ordinations we all received the chalice and paten as the Bishop said: “Understand what you do, imitate what you celebrate, and conform your life to the mystery of the Lord’s Cross.” On the Cross Jesus is offering Himself with the very compassion that transforms the suffering of the world into a cry to the Father. We must learn to accept more profoundly the sufferings of pastoral life which is entering into the mystery of Christ. Rejection of the cross breeds mediocrity. On Good Friday the Bishop and Priests are invited to kiss the Cross first, to give our people an example of faithful discipleship that takes up the Cross each day to follow Christ our Master. I am also mindful that when a man is installed as a bishop, the first thing the Church demands of him is to kiss the Cross. Indeed when I think of my own installation here in the Cathedral of the Holy Cross, everything is kind of a blur. On that fateful day, I entered the Church passing through demonstrators and a crowd of reporters. Then, following the ancient ritual, I banged on the door with the crosier and stepped into a packed Cathedral. I was in a daze. However, I can still hear plainly the voice of a Master of Ceremonies, trying to rouse me from a state of stupor, saying in a stage whisper: “Kiss the Cross!” Outside there was so much turmoil. The love and faith of the people in the cathedral gave me the courage to kiss the cross. Jesus didn’t suffer and die so that we wouldn’t have to. He suffered and died in order to endow our sufferings with the redemptive value, something they would never possess on their own. He suffered and died in order to invest his love with us. He did this so that our love, while not diminishing our suffering or sparing us from pain, will transform pain into holy passion, suffering into sacrifice.

Yet it is not the magnitude of Christ’s suffering that saved us, but rather the magnitude of His love. Love turned His suffering into an offering at the Last Supper, and that love is the Eucharist. It is the Eucharist that transforms Calvary into a sacrifice rather than merely an execution. There the Cross of Jesus turned death upside down. Death is the moment we usually associate with loss of life, but Jesus made it the occasion of giving life. Jesus gave His life freely and fully. He transformed it into a gift, a prayer, and a sacrifice. As we continue to kiss the Altar, the Gospel, the People of God and the Cross, let us not allow our kisses to be routine or perfunctory, but rather let our kiss be a striking gesture of the profound loves that define us as Catholic priests. ###### |

|

|

Photo credit: George Martell/Archdiocese of Boston

|

|

|

Photo credit: George Martell/Archdiocese of Boston |

|

About the Archdiocese of Boston: The Diocese of Boston was founded on April 8, 1808 and was elevated to Archdiocese in 1875. Currently serving the needs of 1.8 million Catholics, the Archdiocese of Boston is an ethnically diverse and spiritually enriching faith community consisting of 286 parishes, across 144 communities, educating approximately 36,000 students in its Catholic schools and 156,000 in religious education classes each year, ministering to the needs of 200,000 individuals through its pastoral and social service outreach. Mass is celebrated in nearly twenty different languages each week. For more information, please visit www.BostonCatholic.org. |

|

|